Respecting Tribal Rights and Right to Consultation: A Key Source of Opposition to Renewable Energy Projects in the United States

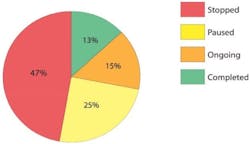

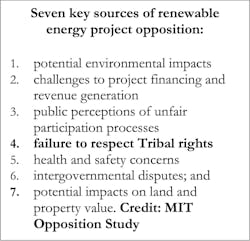

Many believe that with the US Congress commitment to reduce greenhouse gas pollution by at least 50 percent by 2030, and the cost to produce green energy becoming less expensive, electric utility companies are well on their way to helping achieve these net-zero goals. But 53 renewable energy project delays and cancellations, between 2005 and 2022, account for almost 4600 MW in potentially lost generating capacity. Among the seven distinct commonalties of sources of opposition to renewable energy development, our MIT researchers saw a lack of early engagement was a recurring theme and more specifically, in the case of tribal nation opposition, the failure to respect tribal rights, including the right to consultation.

Tribal rights in renewable energy development

Many Tribal nations support renewable energy and see it as a legitimate economic development opportunity. Our findings suggest current federal and state regulations governing renewable energy development, notably the guarantee of consultation, frequently neglect Tribal rights, including the right to sovereignty and the right to self-determination. Opposition and concerns arising from such disregard during renewable energy project development occur in 23 percent of our cases, but disproportionately affect more than one third—37 percent-- of the total generation capacity at risk in our dataset.

While Tribes retain inherent powers of self-government and national sovereignty, their relationship to the federal government is guided by Federal Trust Responsibility, which asserts that matters affecting Tribes are under federal government control. In tribal land and wind farm report by University of Michigan professors Michael G. Zimmerman and Tony G. Reames in 2021 notes the procedural effects of this failure and its impact on wind energy development. Our study finds that an impact of this relationship (and similar dynamics involving energy companies) is that even when consultation guarantees are upheld to their full extent, there can still be conflict because consultation does not equal consent, and that's what the Tribes are seeking.

National environmental laws regulating renewable energy development include the National Environmental Protection Act (NEPA, the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) and the Federal Land Policy and Management Act (FLPMA). Each stipulates participation requirements for the general public and consultation for Tribal nations. As of May 1, 2024, the Council on Environmental Quality (“CEQ”) published the final version of Phase 2 of its National Environmental Policy Act (“NEPA”) rulemaking (“Phase 2 Rule”). Under 40 CFR of NEPA, the general public is guaranteed participation through a comment period mandatory review. Comments must be responded to in the final draft of the environmental impact statement. It is also required that environmental review documents prepared by federally recognized Tribes be considered in the preparation of NEPA assessments. Legal guarantees of Tribal consultation aim to give Tribes a role as partners.

However, these measures are often poorly or inconsistently enforced by federal and state agencies, as well as developers. For example, in 2010 the Quechan Tribe successfully sued the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) for failing to consult them about the development of the Imperial Valley solar park which threatened to damage ancestral grounds and cultural sites. Environmental impact statements prepared by the California Energy Commission indicated that the site threatened the most extensive set of cultural and archeological resources of any of the large solar projects proposed in the California Desert. A Federal judge ruled that BLM had, indeed, violated consultation requirements under NEPA, the National Historic Preservation Act, and the Federal Land Policy and Management Act, put cultural and spiritual resources in jeopardy, and delegitimized the role of environmental impact statements.

Similarly, in May 2015, the Riverside County Board of Supervisors of California voted unanimously to approve the 3660-acre, 485 MW Blythe Mesa Solar Project. The Environmental Impact Assessment, prepared jointly by the County and the BLM two months prior, did not identify any significant or unavoidable risks to cultural resources under the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA).

The Colorado River Indian Tribe (CRIT) filed a lawsuit against Riverside County, the County board of supervisors, and the project developer, Renewable Resources Group, for their approval of the Blythe Mesa Solar Project on Tribal lands of ancestral and cultural significance. The Tribe asserted that the county violated CEQA (California's state environment impact assessment law) by failing to mitigate or analyze the impacts of a solar project on the Tribes' ancient trails, artifacts, and landscapes. They claimed that their extensive comments on the project sent to the county during the public comment period were not adequately addressed. This suit was accompanied by a complaint filed by the Tribe against the Department of Interior for similar inadequacies under NEPA and a lack of adequate consultation. Still, the judge ruled in favor of the defendants (Colorado River, even going so far as referencing President Obama's Climate Action Plan that set a goal of approving renewable projects accounting for 20,000 MW on public lands by 2020. Therefore, the project moved forward and is currently operational. In this case, the judge saw national renewable energy targets as more important than Indigenous culture and people. Although it is certainly important that we transition to more renewable energy, there are many ways to do that. The goal need not supersede the right of Tribal peoples.

Further study shows that it is quite possible to uphold consultation guarantees while protecting the natural environment, but legal interpretations often remove the mandate to do so. Terra Gen proposed a wind energy project in California's Monument and Bear River Ridges. The Wiyot and Yurok Tribes raised concerns that development on the Ridge, a sacred high place to the Wiyot Tribe, could significantly impact hallowed sites and the habitat of the endangered Condor. An alliance formed between the Siskiyou Land Conservancy, the Wiyot Tribe and conservation groups opposed to the project. For the county supervisor, Tribal concerns were the “sticking point.” He wanted to support the project but not if it meant adding to the generational trauma suffered by Wiyot tribal members by forever altering a “culturally important” landscape”.

The Take-Away

Opposition to renewable energy does not typically originate from only one source. This means that incorporating all stakeholder perspectives from the outset of a siting process will probably save time and money. Better to deal with perceptions of possible risks and potential benefits before opponents have made up their minds, and banded together, to block the project. While some perceptions are not evidence-based, they still need to be taken seriously. If ignored, they can trigger wider opposition and ultimately delay or block what many might view as valuable projects. Our findings also show that both the cultural and financial value of land need to be considered in the siting of renewable energy facilities.

Finally, jurisdictional disputes among regulatory bodies and between the US government and Tribal leaders must be tended to apart from general government requirements regarding public participation. Mandatory consultation with Tribes cannot be satisfied during more general public engagement efforts. Not all Tribes govern themselves in the same way, so meaningful consultation may involve, for example, interaction with a Tribal council in some cases, individual Tribal leaders in another, or some other way determined by each Tribe.

Renewable energy development is not likely to occur in an equitable and just way without Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) at an absolute minimum, a ‘check the box’ requirement for both agencies and developers.

About the Author

Lawrence Susskind

Lawrence Susskind is the Ford Professor of Urban and Environmental Planning, Department of Urban Studies and Planning, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Professor Susskind is also Director of the MIT Science Impact Collaborative (scienceimpact.mit.edu). He is Founder of the Consensus Building Institute, a Cambridge-based not-for-profit company that provides mediation services in complex resource management disputes around the world. He also was one of the Co-founders of the interuniversity Program on Negotiation at Harvard Law School, where he now directs the MIT-Harvard Public Disputes Program.

Jungwoo Chun

Jungwoo Chun is the Lecturer of Climate, Sustainability, and Negotiation at the Department of Urban Studies and Planning (DUSP) at MIT Science Impact Collaborative. His research and teaching engage multiple dimensions of climate change and sustainable cities with a particular focus on public dispute mediation, just energy transitions, and social sustainability. He currently teaches 11.255 Negotiation and Dispute Resolution in the Public Sector and holds a Ph.D. in Environmental Policy and Planning from MIT DUSP.