Germany Risks Blackouts with Speedy Coal Exit

(Bloomberg) -- Germany’s plan to exit coal could lead to power shortages early next decade as not enough new plants are being built.

The phaseout of the world’s most widely used power fuel coincides with the ongoing shutdown program of nuclear plants. Together they will remove almost a third of the capacity in Europe’s biggest market in the next three years. The shift away from traditional power sources is a key pillar of Angela Merkel’s environment policy focused on reducing carbon emissions, an area where Germany is lagging behind its 2020 target.

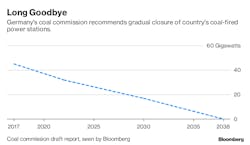

In January, the nation’s coal commission recommended that Germany reduce its coal capacity from 43 GW in 2017 to 30 GW in 2022, and complete the exit by 2038. At present, coal and nuclear energy account for about half of the country’s electricity generation.

The policy recommendation is meant to help Germany achieve its targets to fight climate change. By backing the Paris Climate Accord, Europe’s biggest economy and carbon emitter signed up to cut pollution by 55% within 2030 compared with 1990. It will notch up a reduction of about 32% by next year.

“I am really insecure about the security of supply,” Tobias Federico, managing director of consultant Energy Brainpool, which has advised the German government and RWE AG, said at a Montel conference in Dusseldorf. “Especially for 2022, it is an issue. I am concerned about the winter of that year. It takes five years to build a power plant and we don’t have that time anymore.”

While some of the capacity gap can be filled by new renewable energy and natural gas plants, it will leave Germany reliant on imports from neighbors. However, some of these other markets are going through their own energy revolutions and are also cutting coal capacity. Consequently, Germany has not been able to attract investments for new gas-fired power plants because of the very low or even negative margins.

“There is no rational reason for a company to build a gas plant right now, because it won’t get returns,” said Federico.

Investments in clean energy in Germany dropped by 31% to US$10.6 billion in 2018 from 2017, according to BloombergNEF. But even if new capacity is added — mainly wind parks in the north — the grid would need upgrading to ship the electricity to the main consuming areas in the south.

“We see security of supply in 2023 endangered in Germany with the recommendations of the coal commission,” said Konstantin Lenz, a business developer at Wattsight, a Norwegian energy consultant. “And politicians are not really aware of that challenge. There is no time to install batteries or new gas power plants.”

Germany’s Bundesnetzagentur, the grid regulator, and the Economy and Energy Ministry didn’t respond to requests for comment.