Powering the Past and Electrifying the Future

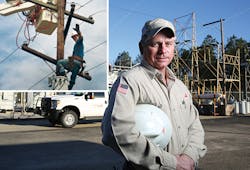

At just 19 years old, Nelson Smith launched his 43-year career in the line trade. Over the decades, the tools, technology and work practices have continuously changed, but he will never forget his first few years in the field — when everything was done by hand.

“We hand dug a lot of holes using A-frame trucks to set the poles,” said Smith, a journeyman lineman for Mecklenburg Electric Cooperative in Chase City, Virginia. “There were no battery-operated tools at all, and we were boring holes with bracing bits. With the advantage of today’s tools and personal protective equipment, linemen will be able to live a lot longer.”

In addition, they can prevent repetitive-use strains and sprains through more ergonomic work practices, enabling them to work longer careers in the field. Jeffrey Roy, a senior supervisor with 41 years of experience for Eversource in Yarmouth, Massachusetts, says the equipment has gotten better and safer as a result of regulations from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA).

“The tools, wire and equipment have all gotten better,” Roy said. “We are still doing the same work that we did a long time ago, but we have different ways of doing it. The biggest improvements are our new trucks, new technology and new equipment.”

Hard Day's Work

In the early days of the trade, linemen climbed poles from morning to night. While the first bucket trucks were invented in the 1900s as cherry pickers, the first insulated bucket trucks for linemen were not commercially available until the 1960s. Then, a decade later, bucket trucks became more commonplace as linemen used them to build and maintain infrastructure in the mountains of Virginia, notes Smith.

Even if a line crew had access to a bucket truck, however, the apprentices often spent their days strapping on their leg gaffs and climbing to the top of an endless number of poles. Roy remembers one thing about his days as a groundsman — climbing one pole after another.

“Our crew had access to a service bucket truck, but I couldn’t use a material handler until many years later,” Roy recalled. “We climbed in the morning, and we climbed in the afternoon. We worked a lot of extra hours to build most of the main lines, but when you are young and in your 20s, it didn’t hurt like it would now.”

Bob Birss, a Canadian lineman who recently celebrated 45 years in the line trade, says back in the 1970s, a transmission lineman did not take his spurs off all day. Instead, he was usually climbing every other pole, hanging travelers, pulling lines or tying in line. If a lineman could armor rod and tie in fast, he would earn top dollar ¾ about $4 per hour in 1971.

“The work was hard, but we were young and tough, or so we thought,” Birss observed. “There were no cranes with baskets, so we used diving boards and a lot of tricks and ingenuity to get the job done. We used brace and bits to drill holes in the big wood poles.”

Lead lineman Randy Tindle, who works for the distribution department at Alabama Power, remembers those days all too well. As a 21-year-old apprentice, his six-man transmission line crew set poles with a bucket truck and a derrick truck. Still, he remembers climbing all day every day.

“I worked with two lead linemen and a hard-nosed foreman who loved to see the bottom of an apprentice’s boots,” Tindle recalled. “There’s nothing like standing on a pole with bracing bits — talk about an abnormal workout. But back then, I was younger and I enjoyed climbing. I had some good trainers and instructors, and we learned a lot. If it was not for them, I would not be where I am today.”

Today, he and the other lead linemen take a different approach to training apprentices how to climb.

“We still climb from time to time, and our guys will climb an average of three poles a week,” Tindle said. “We try to get them some experience, and we make sure they know how to get up and down the pole, because they won’t be able to get a truck into every area.”

The trainers, however, do not make the apprentice climb just for the sake of climbing. The utility now has more training programs to teach the linemen proper climbing techniques. Transmission crew leader Willie Turner says when he first entered the apprenticeship program at Alabama Power, he learned primarily through on-the-job training.

“A lot of things have changed,” Turner said. “Poles are a lot higher, and we don’t do a lot of climbing unless it’s necessary.”

In addition, the engineering department is designing the new distribution infrastructure in spots more easily accessible to linemen and their bucket trucks. That way, they can maintain poles more efficiently and perform trouble-related tasks.

In addition, all linemen must wear full fall protection to comply with the new standard enforced by OSHA. When he was an apprentice, Turner says he was expected to free climb. If he could not have climbed a 70-ft pole, then he would not have made it in the transmission department. Now everyone on the crew — from apprentices to journeymen — must be fully protected from the bottom to the top of the pole to prevent falling or slipping.

Because he had free climbed for so long, Turner says it took time to get used to wearing full fall protection rather than free climbing.

“It takes a lot more effort, but I think it is a whole lot better,” Turner said. “You don’t have to worry about cutting out and falling to the ground.

Spotlight on Safety

Over the decades, line work has become safer not only through improved fall protection devices and hands-on training, but also through changes in regulations and safety standards. In the beginning of the line trade, linemen earned low pay at $0.15 to $0.20 per hour, worked long weeks at 12 hours seven days a week, and endured dangerous work conditions, according to the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW) Local 104.

At that point in history, lineman fatality rates skyrocketed as a result of no safety training, no apprenticeship programs and no standards. In fact, the IBEW found, in certain parts of the country, one out of every two linemen died, and the fatality rates nationally were twice as high as other industries. As a result, the IBEW was formed at the end of the 1800s to put an end to the inhumane working conditions of linemen.

Even so, line work is still rated as one of the top 10 most dangerous careers. For the first 20 years of his career, Smith remembers many linemen experiencing accidents as a result of never-ending work hours. When he first started, it was not unusual to work 36 to 50 hours, but now, crews only work eight to 16 hours at a stretch.

“It’s a good thing to limit the work hours, because if you are not alert mentally and are physically exhausted, that can contribute to an accident,” Smith explained. “I’m not sure when I saw that come into play, but it has definitely evolved over the years.”

Smith experienced the danger of working too much overtime back in 1986. After clocking 37 hours straight restoring power following an electrical storm, he made contact with 7200 V and was electrocuted, an accident that forever changed his view on safety.

“I was working in the bucket, and I remember losing my balance, falling and making contact with the wire,” Smith recalled. “No one on the crew knew anything about CPR or first aid, but a retired nurse happened to drive by and she performed CPR on me right in the middle of the street.”

After the ambulance arrived, it was estimated Smith had been dead for four-and-a-half minutes before he arrived at the emergency room. Eight months later, after recuperating at the burn center in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, Smith was back at work again. Since that time, safety practices have changed dramatically; today, there are monthly safety meetings and daily tailgates, which were unheard of 20 years ago, Smith notes.

“Back then, you would come to work in the morning and hope you would make it to quitting time in the afternoon,” Smith recalled. “Even today, the fatality rate still scares me. It is uncalled for. It is unreal the number of guys who are still getting killed in this industry, and I think complacency has a lot to do with that.”

Smith tries to work with apprentices at Mecklenburg Electric Cooperative to teach them the safe way to do their jobs. Because of what happened to him as a young worker in the trade, Smith feels he is more safety oriented than a lot of other linemen.

“Safety should be 99% of the thought process in this industry,” he explained. “I am trying to get our younger guys focused on a different direction than just money, especially on storms. You can’t be there thinking about the dollar bill.”

To minimize or eliminate the number of linemen accidents and fatalities, electric power utilities are working to change the culture. For example, Alabama Power created a companywide Target Zero program, which has reduced its on-the-job accidents by two-thirds.

“It used to be acceptable in the line trade to have accidents, but now it is not,” Tindle said. “I think once everyone bought into it, things started to change.”

When Turner first started, he says the younger linemen were expected to follow a “do-as-I-say” approach from supervisors. Now that the program has been implemented, everyone on the jobsite is encouraged to speak out if something is unsafe.

“It’s a big change, and it takes some getting used to,” Turner said. “Within this program, we are our brother’s or sister’s keeper, and everyone on the job is important and has a say. Before we start the job, we stop and address any problems and don’t continue with the work until the issue has been resolved. I tell the youngsters to do their jobs safely, and I work with them and show them how to do certain things. I’m not going to put them in a situation they are not comfortable with.”

The utility also is requiring every field employee to participate in job safety briefings, which it started back in 2003. On each and every job, the team identifies hazards on the jobsite and designates a person to call 9-1-1 and be in charge in case of an emergency. Also, the crews always know where the closest hospital is located to a jobsite, and they inspect their first-aid kit monthly to ensure it is well stocked. In addition, the utility recently equipped each line truck with an automated external defibrillator in the event of a cardiac arrest and ensures all of its employees are up-to-date on first-aid and CPR training.

Now that the utility is actively engaged in energized work, Alabama Power also has changed its work practices and invested in additional personal protective equipment for its field workforce. Today, its linemen wear flame-retardant clothing and rubber gloves while working live. Years ago, however, Tindle remembers that linemen throughout the industry wore a lot less protection.

“We would operate a bucket with a belt around our waist, and wear regular jeans and T-shirts, and nobody would say anything,” he recalled. “Now side shields are mandatory on safety glasses, and whenever we operate a bucket, we must wear a full-body harness, long-sleeved flame-retardant shirt and pants, and electrical hazard-protected boots.”

They also are instructed to inspect the trucks, lines and adjacent poles on each side before doing energized work and cover all paths to ground.

“We take time to visualize what we are doing because we know the importance of doing the job correctly and safely,” Turner said. “When it comes to rubber gloving, every job is different, and no two jobs are the same.”

Tapping into Technology

Veteran linemen not only have seen dramatic changes in safety equipment and practices but also in tools and technology. Birss says while installing aerial markers on river crossings, he often thought about how the linemen before him worked with no modern tools and little hydraulics in the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s.

In the even earlier history of the line trade — back in the 1890s to 1920s — linemen strung thinner copper wire from 30-ft to 40-ft telephone poles, only worked with one or two circuits and performed a significant amount of rigging, notes Jason Townsend, a journeyman lineman for Meade Electric in Chicago, Illinois. Also, wearing felt caps rather than hard hats, linemen worked on six- or eight-man bull crews, hand carried all the poles into jobsites and relied on mules to carry their supplies.

“It was hard manual labor, and if the linemen didn’t do what they were told, they were sent down the road,” said Townsend, who is an avid collector of antique insulators, utility signs and historical lineman postcards. “Today, a lot of the work is done by our big machinery, and rather than having a lot of guys on the crew, we work on a three-man crew, but we still have a lot of work to get done.”

Today’s linemen must work with heavier poles, thicker wires, higher voltages, longer spans and larger loads than their predecessors. At the same time, however, Townsend says the bucket trucks have gotten smaller and more versatile, the backyard machines are able to set bigger poles in the backyards and a lot of helicopter work is going on nationwide.

Smith agreed, saying today’s modern heavy equipment has made the physical part of the job much easier, and the technical end of the line trade is changing every day.

“In the late 1970s, the industry started to see a lot of the changes with technology,” Smith said. “Now that we have hydraulic power tools and ATVs, a lot of the physical strain has been taken away.”

Over the last 17 years, Townsend believes hand tools have come a long way as far as usability and ergonomics. When he started working as a groundsman and later as a lineman, the utility he worked for started to transition from the hand hydraulic press tools to battery-operated tools like presses from Huskie Tools.

Mecklenburg Electric Cooperative also has continually invested in new tools for its field workforce to improve linemen’s productivity. Oftentimes, Smith says he and his other team members have discovered new technology at the local rodeos and the International Lineman’s Expo and brought information on these new products to the management team. For example, each year many of the exhibitors offer lighter and more powerful battery-operated tools with a longer battery life and more functionality.

“The battery-operated tools have just exploded,” Tindle observed. “The battery-operated cutters, presses, impact wrenches and drills are saving elbow, wrist and shoulder injuries. In addition to being faster and more productive, they are also a lot safer.”

Beyond hand tools, modern communications technology has revolutionized the way linemen communicate with one another, navigate directions to a jobsite or submit reports. While linemen once relied on brick-sized radios and paper maps, they are now able to pull up data right on their iPads from the field. While Tindle says that it was a struggle for him to learn how to use the technology a year ago, it has now become an essential tool for him in the field. On the transmission side, Turner’s crew heavily depends on the iPads.

“When I was coming up through the trade, the older linemen always knew where the lines were and how to get to them,” Turner recalled. “Now we can pull up a map and find out the easiest way in and out of an area. It is tremendous and has helped a lot.”

Tindle says when he first started out in the trade in 1985, he never anticipated the technology would advance so significantly during his career.

“The knowledge and technology is forever changing,” Tindle said. “We take today’s material and devices, and we install them and put them in place and learn how to use them, and then there’s something better on the market.”

While the line industry will never stop evolving, linemen are continually learning on the job, upgrading infrastructure and installing new lines to serve generations to come. At the same time, however, they have not forgotten the pioneers of the line trade, who helped to first power the country.

About the Author

Amy Fischbach

Electric Utilities Operations

Amy Fischbach is the Field Editor for T&D World magazine and manages the Electric Utility Operations section. She is the host of the Line Life Podcast, which celebrates the grit, courage and inspirational teamwork of the line trade. She also works on the annual Lineworker Supplement and the Vegetation Management Supplement as well as the Lineman Life and Lineman's Rodeo News enewsletters. Amy also covers events such as the Trees & Utilities conference and the International Lineman's Rodeo. She is the past president of the ASBPE Educational Foundation and ASBPE and earned her bachelor's and master's degrees in journalism from Kansas State University. She can be reached at [email protected].