Maintaining and Repairing Aging Lattice Towers: Strategies for Safety and Cost-Effectiveness

Key Highlights

- Maintaining existing lattice towers is crucial due to their age, corrosion, and inability to withstand extreme weather, requiring careful evaluation and reinforcement.

- Decisions to repair or replace structures depend on cost, safety, load capacity, and liability considerations, with repair often being more economical when feasible.

- Structural evaluations prioritize worker safety, assessing transient loads, damage sources, and environmental conditions before any disassembly or repair work begins.

- Temporary stabilization methods like internal bracing, guyed supports, and cranes are essential to safely remove damaged members while maintaining tower stability.

- Finite-element analysis provides precise modeling of tower behavior under various conditions, guiding safe removal and reinforcement strategies for complex scenarios.

While it is good that expanding the capacity of the electrical grid is receiving lots of attention these days, maintaining our existing infrastructure must not be ignored. Thousands of lattice towers, the structure of choice for mid- and high-voltage transmission lines for a century, are long past their original design service life. Many of these structures require maintenance to repair corrosion or damage to avoid costly outages. In addition, most were not designed for increasingly extreme weather events and require strengthening to be brought into compliance with modern load and resilience requirements.

To accomplish this, partial disassembly of in-service lattice towers is an option that can be considered. Unfortunately, while lattice towers were designed and tested to be stable while intact, none were checked for partial disassembly while fully loaded and energized. An engineering analysis is required to mitigate the risks associated with this type of work.

Strengthen In-Place VS. Remove and Replace

This article will not go into a detailed financial analysis, but it is often more cost-effective to repair or strengthen existing lattice towers versus replacing them with new structures. Most utilities have their own cost data regarding new structure costs. Those costs must be compared against key factors for repair or strengthening which include:

- Can the work be performed with the line energized, or is an expensive outage required?

- Are internal or external supplemental supports required?

- Can the work be performed with wires attached to the structure?

- What will the final design life be as compared to a new structure?

- What are the current and future liability risks, factoring in worker safety?

Part of the decision on whether to keep or replace the entire structure must include whether the damaged piece will be patched while it’s still on the tower or removed and replaced with a new one. Each utility has different levels of risk tolerance and assigns different weights to the liabilities associated with either option. Placing too high of a weight on the risk involved with removing damaged pieces opens up other sources of liability and may require replacing a tower that can be saved.

Going with a repair-only approach may help in limiting immediate liability, but it also limits future options. Many utilities have language in right-of-way agreements requiring landowners to pay for any damage they cause to structures. Restoring a long-damaged tower to a like new condition makes it easier to require the landowner to pay for future damage. In addition, an obviously damaged and repaired tower near the site of a wildfire ignition could be used as evidence of liability during litigation.

Structure Evaluation

Worker safety is paramount during any field activity. Even if a structure has remained standing for an extended period with significant damage, the engineering evaluation and analysis will show whether it is safe for work to start. The damaged member(s) may be providing just enough strength for stability and cannot be removed, or a worker on the structure could slip and apply a fall arrest load at the wrong place.

The evaluation must determine whether the source of the damage was transient or if it is still present and applying load to the structure. Examples of transient loads include vehicle impacts, bullet holes, or cows that have used the tower as a scratching post. Broken wires that have damaged a crossarm must always be mitigated before proceeding. Damage caused by shifting foundations is especially dangerous. Such shifts could place the entire tower in a state of extreme stress that could cause serious injuries to workers in the area if the wrong pieces are removed.

The engineer must establish reasonable maintenance weather conditions for the repair work; the work will not be performed during a hurricane or blizzard. Locations with constant high winds require a higher maintenance wind pressure than a sheltered southern swamp. The engineer must then establish whether the tower will remain stable under the chosen wind pressures with any pieces removed and must identify the location(s) of safe fall arrest attachment points or whether direct climbing is allowed at all.

If the evaluation and analysis show that it is not safe to work on the structure, or that the cost to make it safe would be prohibitive, replacement may be the best option.

Stablization Options

Several stabilization options are available to ensure that structures remain stable and safe when removing pieces of a loaded tower. All are temporary and are only installed for enough time to perform the work before being removed. In some cases they can be used to quickly stabilize a critically damaged tower to give the engineer time to design a permanent repair.

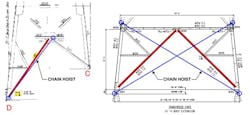

The easiest and cheapest to install is internal bracing composed of chain hoists or hand winches. They can replace the full strength of a piece in tension or adjust the tower to remove the stress from a piece in compression.

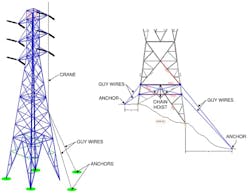

External stabilization is more expensive but is sometimes required. Down guys are common, but installing the anchors can be problematic in environmentally sensitive or rocky areas. Guyed stub poles can be used to replace the strength of a main post leg or as a temporary “field crane” to support a tower. The most expensive option is a crane because using one usually requires a circuit outage. A crane large enough to carry the entire weight of the tower and wires may be required, or a smaller one that only needs to provide a small uplift force to a single leg.

Regardless of overall tower stability, no piece under active load must ever be removed without removing the load first. This is easy to spot; if the bolt doesn’t slide easily out of its hole, it is under stress, and things could go very wrong very fast if it is removed. The load in the piece must be redistributed before removal.

Common Replacement Scenarios

Redundant braces are used to provide bracing to other pieces; they are not designed to carry any load on their own, and they are the easiest to replace. Stabilization is rarely required to replace a redundant brace on light tangent structures under maintenance conditions; simply remove the damaged piece and replace it. Heavily loaded structures such as anchor towers may require supplemental support. Either way, the effects of removing even the smallest brace should be evaluated before the work is performed.

Leg diagonal braces are by far the most damaged piece on lattice towers because they are near the ground, usually slender, are frequently hit by right-of-way maintenance equipment or other vehicles, and can be easily damaged by corrosion. Removal of leg diagonals requires two types of checks. First, any redundant braces between the leg diagonal and the main post leg will be removed along with the diagonal. As leg buckling is not recommended, the reduced capacity of the now-unbraced leg must be checked. This may require supplemental external support to remove load from the area. Second, establishing a replacement load path for the damaged member is required before removing the piece. It is frequently possible to find an alternate load path within the remaining tower, but an inexpensive internal support such as a chain hoist could be the answer.

A special case with leg diagonals is the inverted “V” or “Delta” configuration. The two adjacent diagonals work as a pair, with one in tension and the other in compression, balanced against each other. If you remove one you remove the entire capacity of the panel. Finding an alternate load path through the remaining pieces on the tower may be possible, but it’s safer to install a pair of chain hoists across the panel in an “X” configuration.

Replacing a main post leg is not as common because they are harder to damage, but is still sometimes required. In addition to resisting the weight of the tower and wires, uplift and transverse supports are often required to resist overturning forces from line angles. Replacing some long post leg pieces requires “unlacing” a large portion of the tower which can eliminate most of the tower’s stability and strength. Careful analysis and external supports are always required, sometimes even lifting the entire tower.

Member replacement becomes more difficult as the member being removed gets higher up in the structure. Evaluating replacement load paths for the member itself, along with any additional members unlaced during the removal, becomes increasingly difficult. Supplemental supports are usually required as well as a detailed finite-element analysis (FEA).

Analysis Methods

Manual spreadsheet calculations are all that are required to replace some piece types for many standard structures. First establish conservative forces from wires and the structure itself, then use basic statics to calculate the forces in whichever piece is being analyzed. This can often be performed much more rapidly than modifying a full FEA model, especially if the FEA model must be created from the start.

But for more complicated structures and scenarios, the most accurate and reliable type of analysis is a finite-element analysis model of the structure. It allows the engineer to quickly analyze the tower under multiple weather or loading conditions and accurately size any temporary supports. This method is required in some scenarios, such as verifying the tower’s stability with multiple members removed.

The FEA model being used must accurately represent reality. Lattice towers are almost always designed as pure trusses that resist forces through axial loads, using relatively slender pieces that are weak in bending. Despite this, bending elements must be used in most FEA models to provide localized stability. For a well-triangulated lattice tower model these bending elements do not make a significant difference in the analysis results. However, for a detailed analysis of a tower with key pieces removed, too many bending elements can create false stability. The model could converge and show acceptable stress levels when the slender pieces would actually fail in bending causing a tower collapse. As many sources of frame action as possible must be eliminated from the FEA model. This may require eliminating some redundant braces that are not braced out-of-plane. A few isolated bending elements that are not connected to other bending elements are acceptable.

The best way to calculate support requirements is to model the support within the FEA model. Internal tension supports, whether pre-tensioned or slack, can be modeled using Cable elements in most commercially available software. Guy-anchor supports and cranes can likewise be modeled as Cable elements. Crane supports can also be modeled as guys; anchor the guy to a primary joint some distance directly above the attachment point.

Finally, care must be taken to model the wind loads applied to the structure. Old “wind on face” loadings that mimic old hand calculation methods and are required by most design codes should be supplemented by additional load cases using fluid dynamics based wind models. These modern wind models more accurately apply wind to all pieces.

It must be stressed again that the safest option is always to attempt strengthening or repair of in-service lattice towers by adding additional members, or to remove existing members after adding the new ones. But strengthening or repair can safely occur even when members must be removed from an in-service lattice tower, resulting in significant cost savings versus installing a new structure. A careful analysis and using safety-first field processes can ensure a high level of confidence for the engineer, owner, and field personnel with minimal risk to all involved.

About the Author

Jason Kilgore

Jason Kilgore is a structural principal engineer in Mesa’s Power Delivery - Transmission and Distribution business unit. He has 19 years of experience with electrical power transmission, plus experience in industrial, commercial, and residential design. As Mesa’s primary subject matter expert in transmission structures and foundations he is involved with solving the more complicated problems discovered by Mesa’s internal design groups and external clients.

Elliott Thaxton

Elliott Thaxton is a licensed PE and has worked for Mesa Associates, Inc. for 8 years with 10 years of experience in engineering. He is a Group Lead in the Power Delivery: Transmission and Distribution (PDTD) Business Unit. He led the tower repair, damaged footing, corrosion mitigation, and fall protection analysis programs for several years. While at Mesa he has gained extensive knowledge in line design, TOWER modeling, structural analysis, and foundation design.