National Grid Tunnels Under Buffalo River

How do you get from one side of the Buffalo River to the other when a boat or bridge won’t do? You go under it with a very large coffee grinder.

In 2018, as part of an ongoing commitment to modernize and improve energy infrastructure and better serve customers, National Grid undertook the project on Ohio Street in Buffalo, building a 422-foot tunnel beneath the Buffalo River. This was the first such project in company history.

The $11 million construction project, which began in November 2017 and was completed the following July, helped the company address future electricity needs.

“This was an exciting project for National Grid,” said National Grid Regional Director Ken Kujawa, who added that there’s been so much new construction, growth and expansion in this part of the city in recent years. We didn’t want to be an impediment to industries and those with growing businesses who have new needs and requirements. As an example, if a new company wanted to build a project here, we didn’t want to tell them, ‘it’s going to be a few months before we can connect you to service.’ Instead, we want to be able to use our improved, modern infrastructure to immediately meet their needs.”

Kujawa added, “Carving a tunnel beneath the river was considered the preferred option when compared to supporting cables across the river, which is 320 feet wide. The tunnel also provided an eye-pleasing benefit, since boaters and residents wouldn’t have to see power lines that were strung overhead.”

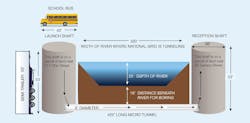

The tunnel connected two shafts, which are located near 511 Ohio Street, to the north of the Buffalo River, and 95 Ganson Street, which is to the south of the river.

The Big Coffee Grinder

The company began the project by lowering a 14-foot, 29-ton tunnel-boring machine into a steel-reinforced concrete shaft on a parcel of land near Bison City Rod and Gun Club, which is located at 511 Ohio Street. The micro-tunneling machine – which works like a giant coffee grinder – bore a tunnel 422 feet long – about the length of one and a half football fields – and six feet in diameter. The concrete tunnel, located 18 feet below the riverbed, was connected to a second shaft on the other side of the river near 95 Ganson St.

Both shafts were 53-feet deep and at least 36-feet in diameter. When finished the steel-reinforced concrete tunnel housed new electrical cables and modern equipment, replacing cables that dated to the 1890s and early 1900s.

After about three weeks, in late May, the machine emerged on the other side of the river into the second steel-reinforced concrete shaft.

Cutting Beneath the River

When representatives from Germany-based Herrenknecht AG provided details about their tunnel boring machine, they compared the remote-controlled, cylindrical slurry machine to a coffee grinder, a comparison the utility officials found apt. The machine was owned by Ward & Burke Construction, Ltd., which is based in Ireland.

Guided by operators at street level, the massive cutter head at the front of the unit is equipped with spinning knives and discs. As the machine inched toward its destination, it excavated an estimated 8,000 tons of soil, chunks of limestone and other obstructions, which were crushed, granulated and mixed with a slurry.

The granules were then pumped upward toward a separation site at the surface. There, the excavated material was treated to be made suitable for use in projects like road construction. Rather than deliver the material to a landfill, it was donated to a developer.

However, carving the tunnel was easier said than done. Ward & Burke engineer Cillian Cotter said that an additional challenge presented itself. He told The Buffalo News in a May 1, 2018, article that the local formation of limestone is “close enough to the strength of granite; it’s extremely hard rock.”

To cut through it and complete the task, he explained, the machine was outfitted with special equipment on its head.

Building in Sections

As soil and stone were excavated, a tunnel was built using a pipe-jacking method. Common for these kinds of jobs, pipe jacking includes use of a hydraulic jacking frame, which is positioned behind the tunnel-boring slurry machine. The frame pushes the tunnel-boring machine and a string of pipe. This way, after stone and soil are excavated, a tunnel is built in sections. It’s a stop-and-go process, which is repeated to lengthen the tube in the tunnel.

The company has used similar tunnel boring machines for overseas projects, but the Buffalo River project marks the first time that National Grid has used this technology in the United States.

After tunnel cutting work was done, workers removed the boring equipment and added conduits to the newly drilled tunnel. Workers then strung the tunnel with electricity cables and filled and sealed with giant manholes both sides of the 53-foot-deep shafts under the river.

Although the scope of the project was immense, including bringing people and resources to Buffalo from all over the world, it’s all neatly paved over. So, unless someone was aware of all the planning, technology and people that came together and left in 2018, no clues remain about the work that was completed or the improved infrastructure that lies well beneath the surface.

But people like National Grid’s Kujawa are aware. And although his customers may not understand the full extent of the work that was completed, they’re certain to appreciate it. That’s because the infrastructure that replaced early 20th century equipment allows National Grid to meet changing customer electricity needs safely and reliably today and at least into the 22nd century.

DAVID BERTOLA works in corporate affairs at National Grid in Buffalo, New York. David earned his bachelor’s degree in English from University at Buffalo and his MBA from D’Youville College.

For More Information

Herrenknecht AG | www.herrenknecht.com/en/

Ward & Burke Construction, Ltd | www.wardandburke.com

The Big Coffee Grinder

The micro-tunnel boring machine is manufactured by Herrenknecht AG, a German construction equipment manufacturer that has its headquarters in Schwanau, Germany.

Herrenknecht AG manufactures a half-dozen different kinds of tunnel borers, each capable of operating in different kinds of geologies, including heterogenous grounds full of sand, clay, silt and gravel, and hard, stable rock such as granite, gneiss or basalt.

In soft soils and mixed geologies, standard or mixed ground cutterheads are used, while a rock cutterhead with disc cutters is used for tunnelling in stable rock formations.

According to the company, the machines are operable in almost all ground conditions and under high water pressures.

The machines are designed to drill holes at a smaller diameter than people can walk through – also known as microtunneling. They can drill tunnels from 0.4 meters to around 4 meters.

The tunneling machine’s cutting wheel is fitted with disc borers and cutting knives to fit the anticipated geology of the ground it will cut through.

Behind the cutting wheel is the crushing chamber. During operation, it is filled with support fluid and the cladding lining the inside of the crushing chamber acts like a coffee grinder.

Larger pieces of soil are crushed until they fit through the machine and are carried away along with support fluid through the slurry line and pumped back to the surface, where it is treated onsite at a separation plant. Clean support fluid is then fed back through the tunneling machine.

A hydraulic jacking frame in the launch shaft or hydraulic thrust cylinders in the shield push the machine forward as it bores.

A port behind the cutterhead allows operators to allow access to the tunnel face. Workers can safely enter the pressurized front through an air lock to remove boulders or change out worn cutting discs.

These machines are guided remotely, with camera systems, lasers and software to guide them along their planned tunnel.

Once each tunnel segment is dug, the shaft is supported by a series of segmental liners that are jacked into place as the machine moves ahead. The liners are lubricated with wet bentonite clay to minimize friction.

These same machines were used to extend the sewage system of the city of Jeddah on the Red Sea in Saudi Arabia, a job which required 30 tunneling machines.

The machines also dug flood protection for Doha, Qatar, tunneling through 4,250 meters of gravel, sand and rock in a project to channel flood waters safely into the Persian Gulf.

In Guangzhou, China, tunnel borers crossed under potentially sensitive urban environments, including streets, rivers and buildings to construct that fast-growing city’s metro network expansion.

In the North Rhine-Westphalia region of Germany, nine microtunneling machines bored wastewater tunnels in the sand, clay and marl of the Emscher area.

The tunneling machine used by National Grid was owned by Irish construction firm Ward & Burke, which has drilled more than 40,000 meters of tunnels of various diameters throughout Ireland, the UK and North America – typically for stormwater and wastewater projects.

About the Author

David Bertola

David Bertola ( [email protected]) works in corporate affairs at National Grid in Buffalo, New York. Bertola earned his bachelor's degree in English from University at Buffalo and his MBA from D'Youville College.