Listen to an audio version of this story on the Line Life Podcast on Podbean.

Randi Blaser grew up in a family of lineworkers, but it wasn’t until she climbed her first pole and later worked her first storm that she discovered a passion for the line trade. She recently topped out at Ameren Illinois, and she said line work can be a rewarding career for women nationwide.

“Women aren’t as strong as men, but women are definitely capable of doing what men can do — they just have to do it differently,” she said. “With the way things are going with the power tools and all the advances that have been made, it’s leveling the playing field for women, and I think that is fantastic. You don’t have to be the biggest dude or the biggest girl to do stuff now. If you’re interested in the trade, you’re mechanically inclined and you can pick it up, you can do exactly what they can do.”

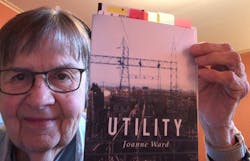

Joanne Ward, who retired from Seattle City Light after four decades in the trade, said the opportunities for female lineworkers in today’s utility industry are just as important and even greater today than four decades ago in their offer of skilled work and stable careers. Ward first started as a line crew helper at Seattle City Light in 1978, and later worked as a high-voltage electrician and crew chief before retiring and publishing the book, Utility, about life in the trade.

“The current workforce is aging out and job openings are, and will, become extremely plentiful,” Ward said. “These jobs will afford a high standard of living, good healthcare coverage, excellent retirement plans and even some defined benefit retirement plans. Women should be educated about them and urged to come get them.”

In the 1970s, women started working in the line trade in different parts of the country. One of those women was Ward, who joined her utility as part of the second wave of an affirmative action program in 1978. She searched for a non-traditional job as an avenue to a higher salary and standard of living. After interviewing with a phone company for an installer’s position, she learned that Seattle City Light was actively hiring electrical helpers. “I liked the idea of working with my hands and working outdoors in a more physically active job,” Ward said. “Those jobs opening up were really a question of equal opportunity for women.”

Currently in the United States, the number of women in line work is still a slim percentage of the overall field workforce. Utilities nationwide, however, are working to increase the diversity of their line crews, and many are hiring their first female lineworkers. As more women work in the line trade, here are four strategies to attract, train and retain female line employees.

1. Take a new approach to training.

Susan Blaser, the lead line technician program coordinator at Metropolitan Community College in Kansas City, is training the next generation of both men and women lineworkers. She said back in 1989, when she started out in the trade, she learned the skill of rigging, which helped her immensely during her career.

“If I couldn’t do something, I would ask everybody, and then I’d take two different ways and figure out what worked for me,” she said. “There’s a lot of technology that has come along, but at some point, there are limits, and that’s when rigging is going to play a critical role.”

About 85% of the students’ time is spent outside on the poles, and the program focuses on how to do things correctly and repetitively to ensure safety. So far, nine women have come through the program, and five of them have become lineworkers, including her daughter, Randi.

When Randi attended the summer climbing portion of the program, she opted to pursue line work as a career. Now that she’s a lineworker, Randi is often in her hooks and on a pole for hours at a time. At 5 ft tall, she said she has had to learn different ways of doing the work. “As far as women, they’re just as equal as men, in my eyes,” Randi said. “Just because we don’t do it your way doesn’t mean we can’t do it at all. We just must figure out a way that we can do it safely. It just might look a little bit different.”

For example, when she’s working on a pole with a taller coworker, they need to learn different ways to work together. “When you’re on the wood pole, and you got someone who is between 6 ft and I’m 5 ft, I can stand up a little higher, and then we can be at eye level with each other, which works out because our feet aren’t hitting together,” she said. “It can be a challenge, but you can still get the work done by the end of the day.”

Alice Lockridge, who was training aspiring lineworkers at Seattle City Light when Randi’s mom, Susan, was starting out in the trade at Kansas City Power & Light (now Evergy), agreed. Many women have told her that when they worked with a taller man, they fit better on the pole. She said there are many ways to scurry into a job position. “If I’m shorter, my feet are up closer to the work and out of the way of those great big feet of the guy that’s doing the work with me,” said Lockridge, who worked as an exercise physiologist at her utility. “My hand goes into little places that they can’t. There’s a need for both sizes of people. Diversity in experience and body size are all of value.”

Another way that women can succeed in the line trade in the early part of their career is to learn one of the basic skills of line work — rope tying. Lockridge founded a group called “Knotty Women,” and she has a booth at high school career days to teach girls how to tie different types of knots and pique their interest in the trades at the same time.

“I think the first day you get on a crew, at least you could run over to the truck and tie a load down and not get yelled at,” she said. “Being able to tie not just a knot — but a real knot — is a great way for an entry-level worker to get into the job.”

Lockridge also said it’s important for women to learn how to use their own body weight to perform line work efficiently and effectively. During her time with her company’s pre-apprenticeship program, she focused on helping people get and keep physically demanding jobs, with an emphasis on helping women get into the trades. She first prepared the pre-apprentices for the physical entrance-level test and then trained them in the gym for three hours three times a week for the graduation test.

“We wanted to make sure they could actually do it and had the physical capacity to learn the skills,” Lockridge said. “The job is hard, and things are heavy, especially in 1988 when I started. Lots of those things have been improved and made lighter, but you still have to get yourself up the pole to work while carrying tools. There’s a lot of physical demands on the body.”

Oftentimes, the physical evaluations may drive off aspiring female lineworkers, but Lockridge asserted that some can do a chin-up with the right physical training. “There’s strength and skill to doing a chin-up, just like cutting wire or tying a knot,” she said. “The reason we use chin-ups is because it shows us that you can manage your body weight. If your feet slip off a pole, you could save yourself until help arrives, or you get your feet back on the pole. It’s a fundamental view of whether you are in the physical condition to be able to start learning in a risky climbing environment.”

Through the training sessions, Lockridge taught the pre-apprentices how to perform the work without getting worn out or injured on the job. “If I had to hoist a bucket of tools up to you on a pole with just my wrist strength, my grip strength and biceps, it wouldn’t make it up 40 ft,” she said. “But if I know how to sit down and use the weight of my behind to make that load go up, I’m a better worker, a longer worker and a less hurt worker.”

Beyond the physical training, utilities also need to consider the different ways in which women learn. No two people are exactly alike, and if the lesson planned isn’t working, it may not be the learner’s fault. The instructors may need to find a different way to present that information. “Stereotypically, women are better readers, and don’t always need just a visual picture of it,” Lockridge said. “Also, we respond really well to positive feedback and not very well to being yelled at and cursed at.”

2. Safeguard women with workwear and PPE that fits.

Due to the work methods and the physical demands of line work, women must also have the proper garments to stay safe and comfortable on the job. Back when Ward started in the trade, she remembers rolling up coveralls at the bottom of her legs.

“I would adjust the shoulder straps as much as I could, but they would still hang low on me,” Ward recalled.

Finding gloves back then was a challenge. Ward said she has a size 7 hand, which she found was to her advantage when she had to work in tight spaces. In certain situations, however, she needed heavy leather gloves. “The first day I came on the job, I had a lovely pair of pig-skin gloves, and they were completely burned through by the end of the day. I learned pretty quickly to get better, thicker, gloves, and I was able to find those that would fit my hand.”

Lockridge, who now serves as an advocate for women in the trades, said female lineworkers often reach out to her for advice and assistance. She said women in the line trade today are still challenged by what clothes to wear, how to find clothes that fit and how to get safety gear that’s made for their shape and size.

“Sometimes their hands are smaller than the gloves,” she said. “I once got a phone call from a woman lineworker apprentice on the East Coast, and she sent me a picture of her doing line work, and I could see her red fingernail polish. She had a guy take a picture of her work, and he didn’t know what he was showing me, but she had no gloves. Her company said they didn’t’ make gloves smaller than a size 8 hot glove, so I went to our stock, pulled out a pair and mailed them to her.”

Randi said it’s a challenge working as a petite woman in the line trade. “I’m like the 1% of the 1% because I’m very petite for my size, and I’m also a woman in a male-dominated field.”

Her utility pays to have her garments altered, which has been a big help, but she said she wants clothes that fit well when she’s out on the job. “I’m not here to make a statement and look pretty, but I’m in these clothes all day,” Randi said. “I want clothes that are comfortable and look good. I don’t want clothes that are baggy and made for men.”

Over the years, as more women have entered the line trade and construction industry, more manufacturers have started making FR garments and workwear tailored to women. These companies understand that women’s workwear is not just smaller sizes of men’s clothing, but specific garments made for women’s shapes and sizes. A few of these companies include Ariat, Bulwark, Carhartt, Dovetail Workwear, Fastenal, DragonWear, Lakeland, Lapco, MWG Apparel, National Safety Apparel, Radians, Rasco, Tyndale and Wrangler.

For women in line work, however, finding boots is also difficult, especially with the current material shortages. “For me to find boots right now is probably slim to none,” Randi said. “I can get a pair of boots that are 16 in. tall that go to the bottom of my knee, but to move around in those all day is not ideal. I’m struggling with just finding an everyday pair of boots. The pair I have right now are worn down.”

Some shoe manufacturers, however, now custom-make boots, Susan added. For example, West Coast Boot Company (Wesco) sizes boots for women lineworkers. Ameren Illinois’ safety department has also been able to order extra-extra small gloves from a company called Kunz. The cut-resistant gloves don’t come into her size back in the storeroom, but her company custom-ordered her a pair as well to keep her safe. Other vendors are also offering gloves in different sizes to fit workers. Youngstown Glove Company offers certain glove styles in sizes ranging from XX-small to 3X-large.

Other essential items for women starting out in the trade are a proper-fitting belt and hooks, Randi added. While many companies may just ask a woman for her height and hand her a belt, Randi said her mom fitted her for her belt and hooks properly, which has made a significant difference in her day-to-day job. “My mom wants that equipment to fit, which is awesome because you’re in that equipment and may be on a pole for six hours,” Randi said. “You have no idea how long you’re going to be on that pole.”

Lockridge said it’s common for women to be proportionally longer in their legs than a man their same height, and as such, the harnesses must fit properly. “Her body harness should be shorter than the guy her same height, but not always,” she said. “Everyone needs their gear to fit their specific body.”

3. Build a support network.

When hiring women in the line trade, Lockridge said there’s a golden rule: Never hire one woman at a time. “That’s a sure way to drown her and virtually ‘prove’ that women can’t do it,” she said. “In the first class at Seattle City Light, there were 10 women hired, and 10 women made it through all their difficulties together and pulled through with each other.”

She can’t say two is a magic number, but she said she prefers the hiring of three women at any one time. The same goes for other minority groups, she said. “Don’t put a token out by themselves to represent all of their gender or group,” Lockridge said.

Susan also encourages the women who are hired by a utility to seek out other women in the line trade. She said it’s essential for women to create a network and have support. “I picked out a small group of individuals that if they told me I was having a good day and I did a good job, I knew in my heart that I had done well to get a compliment from them,” she said.

Today, the women in the line trade can connect online through social media groups with other females in the trade. Susan, who is a member of a Facebook group called Line Ladies, said she didn’t have that option back when she was a lineworker. “Social media wasn’t around,” she said. “I was one female at one location in Missouri, and there was no way of networking or getting that mentoring.”

Randi said she follows a few groups on social media, but she focuses more on connecting with local female lineworkers in her area, including those women who have gone through her mom’s training program. Having a support network will also help tremendously when it comes to storm season. As a freshly topped out lineworker, she said she’s often at the top of the list when it comes to callouts for storm work. Her mom lives four hours away and can help with her one-and-half-year-old twins, and she’s also found friends who can provide childcare in the Illinois area, including a sitter whose husband works for Ameren and a family who “adopted” her and her son and daughter.

4. Create awareness of job opportunities for women in line work.

To encourage more women to consider careers in line work, Susan said there needs to be more education and awareness about opportunities in the trades. “Parents don’t raise their kids to say, ‘when you grow up, you’re going to be a lineman,’ she said. “Schools also don’t promote that.”

For example, she was just at a career fair for school counselors, and she set up a table for MCC’s lineworker training program. Most of the counselors flocked to the fire, police and nursing tables, but few came over to visit with her and learn about the opportunities in line work. By attending her 12-month program, however, her students can earn a high salary even starting out as an apprentice.

“I just don’t think women understand that it’s something they can do, and they can be supported in, and they can be successful at,” Susan said.

Ward agrees, saying there needs to be a culture change at the high school level to advertise the need for young women to participate in technical training. Beyond that, she said the entire culture of the country needs to shift. “This country has traditionally disregarded women as capable of, or sees them as uninterested in, non-traditional trade work,” she said. “I think we now need a concerted effort from the federal to the local level to reframe the societal need for lineworkers that shows the need to be great enough to require both women and men as lineworkers for utilities.”

When companies approach Lockridge to ask her how they can hire more women, she asks them to send her the documents to see their advertisements and graphics. “It all said, ‘we only want boys’ in vague words, but women can read that in the wording. Put women in the picture on your graphic, take the word, ‘man’ off the advertisement and logo and hold recruiting sessions that are selectively geared toward women.”

She advises companies to invite women to come in first by themselves or with a group of women and give them insider tips from people who are experienced.

Lockridge said in today’s utility industry, the jobs are still available — for the right women who are willing to put in the work. “There’s open jobs and lots of opportunity for a woman,” she said. “The door isn’t open very wide, but the right women pioneers will still be kicking the doors in.”

Amy Fischbach ([email protected]) is the Field Editor for T&D World magazine.

Women on the Line: Four-Part Podcast Series

T&D World's Line Life Podcast, which is sponsored by Huskie Tools, highlighted four of the women featured in this story for the "Women on the Line" series. Listen to each episode by clicking on the links below.

What You Need to Succeed as a Woman in the Line Trade

After gaining experience either working in the trade and/or training lineworkers, the four women featured in the “Women on the Line” series on the Line Life Podcast share 10 tips for women considering careers in the line trade.

1. Have a thick skin. When she first started out in the trade, Susan Blaser spent a lot of time, energy and frustration trying to prove to people that she was just as good as some of the other guys in the field. She eventually learned to not worry about other’s opinions and not underestimate her own abilities as a lineworker.

2. Find a mentor. Learning can be frustrating for anyone, male or female, Blaser added. Try not to get discouraged and find others who want to train you and make you the best lineworker you can be. Joanne Ward agreed, saying throughout her career, she found crew members who were willing to train and mentor her.

3. Get a support team. “These should be folks you can call at any hour, in any mood (not just sunny-day friends, but instead bad-day friends who want to hear the truth and can listen if you cry or curse!,)” Alice Lockridge said.

4. Secure dependable transportation. If you want to be considered a valuable worker, you must find a way to get to work, Lockridge added.

5. Trust in your own skills and abilities and practice positive self-talk. Be as kind to yourself as you are to your friends, Lockridge said.

6. Focus on physical fitness. To succeed in the line trade, aspiring lineworkers must be able to be in shape and ready to perform the duties of the job. A pre-apprenticeship program may be a good place for women to start in the trade, Ward said. Randi Blaser agreed, saying her mom’s line technician training program provides women with the support they need to succeed in the trade.

7. Learn how to climb. At Metropolitan Community College-Kansas City, one of three semesters is just focused on climbing.

“We have the students come in, and they’ll decide whether this is what they want to do or not,” Susan said. “Sometimes they self-select out when it’s not really what they expected, and they’ll decide on a different career path.”

8. Show respect for the experience of your veteran lineworkers. “You need to be as friendly as you can, and be ready to help, be useful, and do the dirty work, which will be asked of you—believe me,” Ward said.

9. Learn leadership skills. During her career, Ward served as a crew chief on three different crews, and she said she learned a lot about leadership that she wanted to pass on to the women coming up in the trade. She said it’s important to make it clear from the beginning that you’re not interested in the my-way-or-the-highway methods. “Also, if you’re a quiet person, learn to speak up loudly enough to attract attention in a crew meeting,” she said. “You have to let your voice be heard.”

10. Connect on social. Join social media groups where you can find a place to talk about your day. Within these groups, the other women can understand your perspective and provide support. For example, Lockridge administers a Facebook page titled, “Women in Linework,” and women in the trade are welcome to join.

Looking Back: Working as a Linewoman in the 1970s

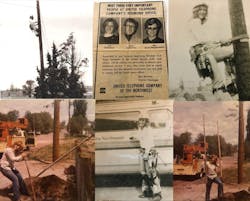

In the early 1970s, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission provided money to hire women and minorities into vocational work. At that time, Todd Cheng said his mom, Judy (Shepardson) Hanson was recently divorced with two kids and no child support, and as a secretary, she was paid $2 an hour.

“The government was maintaining a program to make sure all rural areas were connected with phone lines, and the United States needed more lineworkers and capacity to surge up and run these rural lines,” Cheng said. “One day, a manager walked into the secretary bullpen and jokingly said, “Do any of you girls want to be a lineman?” My mom raised her hand and asked, ‘How much an hour?’

His mom had the potential to earn a dollar more per hour than she earned typing 90 words a minute, and she got the job.

“She spent the weekend bloodying her calves learning how to turn high heels into climbing spikes and scurry up telephone poles,” Cheng recalled.

His mom became the first linewoman at United Telephone Company of the Northwest with its OJT/apprenticeship program. Cheng remembers growing up with the stories about her job and the task lists.

“She climbed poles, dug holes, managed contractors, and projects,” he said in a Women’s History Month tribute to his mom and her grit on LinkedIn. “She has always overcome barriers and used her persistence to step forward, climbing up, digging out and overcoming.”

As an apprentice lineman and grunt on the line crew, Hanson said she learned how to climb 45 ft to 90 ft poles, string cable and hand dig holes 6 ft deep when the auger couldn’t break through the rock. At 5 ft tall and 100 pounds, she was able to maneuver into tight spaces and had more manual dexterity than some of her coworkers.

“I was muscular for a little gal,” she said. “I was also a tough nut and was like the Unsinkable Molly Brown.”

She said she faced challenges as the first woman to work an outside plant job, and she advises current and future women in the line trade to not tolerate discrimination, have a tough shell, be fit and get proper training for the job.

“At that time in central Oregon, women were expected to milk cows, put food on the table and make babies,” she said. “The women didn’t work in the outside plant. The men didn’t know what to do with me, but I learned how to talk like a lineman, and I loved the work and being able to be outside.”

She eventually got remarried and had another child and worked as an installer for about four-and-a-half years for her company in Oregon. She said she’s proud of the legacy and example she set for her children.

“They learned to not put up with anything, do the best you can and finish strong,” Hanson said.

Taking a Global Perspective on Training Women in Line Work

In the United States, women have worked in the line trade for decades, but around the world, women are just starting to train for careers in line work. For example, the country of Colombia just had its first-ever intake of apprentice linewomen. ISA, Latin America’s largest energy transmission company, is partnering with Tener Futuro Corporation for the year-long pilot project.

After The Guardian published the story, “Girl power: Colombia’s first female electrical line workers train to keep the lights on” by Soraya Kistwari, Olivia Wilson, a journalist for BBC Business Daily, decided to take a global look at women in the line trade for a mini radio documentary.

She not only interviewed some of the trainers and trainees for the program in Colombia, but she also interviewed Rosie Vasquez, one of the first women lineworkers in the United States, and experts in Pakistan, which currently does not have any women in the line trade. She also mentioned T&D World’s Line Life podcast and covered the opportunities and challenges for women in today’s industry. To listen to the full episode, visit https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/w3ct4n7z

About the Author

Amy Fischbach

Electric Utilities Operations

Amy Fischbach is the Field Editor for T&D World magazine and manages the Electric Utility Operations section. She is the host of the Line Life Podcast, which celebrates the grit, courage and inspirational teamwork of the line trade. She also works on the annual Lineworker Supplement and the Vegetation Management Supplement as well as the Lineman Life and Lineman's Rodeo News enewsletters. Amy also covers events such as the Trees & Utilities conference and the International Lineman's Rodeo. She is the past president of the ASBPE Educational Foundation and ASBPE and earned her bachelor's and master's degrees in journalism from Kansas State University. She can be reached at [email protected].