Rodeo Recollections: History of the International Lineman's Rodeo

Thirty-seven years ago, inspiration struck Dale Warman as he was talking to future linemen at the Manhattan Vocational Technical School in Manhattan, Kansas. For centuries, cowhands had competed in rodeos to practice and improve their skills before their families and communities. Why not linemen?

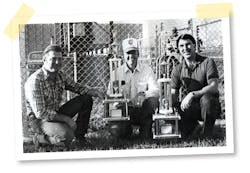

Two years later — in 1983 — Warman teamed up with Kansas City Power & Light (KCP&L), Kansas Gas & Electric, Kansas Power Light and Board of Public Utilities to organize the first Lineman’s Rodeo at the technical college in the so-called Little Apple. Twelve teams, totaling 36 linemen, came out to compete.

Thirty-five years later, the event has grown to become the International Lineman’s Rodeo, attracting linemen from all over North America and the world to compete on the global stage. Over the years, linemen from Canada, Jamaica and Ireland, for example, have competed alongside the American apprentices and journeymen linemen.

The Early Days

The first teams and winners hailed from KCP&L. Since then, the utility has served as a friend of the rodeo, noted Martin Putnam, program manager-field operations for KCP&L and a member of the board of directors for the International Lineman’s Rodeo Association (ILRA). After helping to run the second year of the competition once again in Manhattan, KCP&L hosted the third rodeo at its Sub One training grounds. By then, the event had doubled in size, and Warman started to receive calls from other utilities that wanted to compete.

Michael Stremel, journeyman lineman for Midwest Energy Inc. in Hays, Kansas, remembers competing in his first rodeo at KCP&L’s training center in 1988. “There were about 35 teams there, and 30 or 40 apprentices, and I competed as an apprentice that year,” recalled Stremel, who has served as a lineman for 32 years and now works as a training manager. “I met people that I still visit with today. There’s a lot of camaraderie.”

During the 1988 competition, Stremel participated in the hurt-man rescue, pole climb and crossarm changeout events. “I realized that my level of training was not what other utilities had, and I didn’t do very well the first time I went to the rodeo,” said Stremel, who has competed in 16 different International Lineman’s Rodeos over the years. “After competing for a second or third time, however, I learned that it was a good learning opportunity.”

These days, Stremel and other linemen from the United States are not just learning from one another. They’re competing with linemen internationally. Although they hail from different regions where practices may differ, the linemen all have safety in common.

“The one reason why utilities support this is because everything we do at the rodeo is based on safety,” said Warman, who retired from his job as a director of field operations for KCP&L and now serves as co-chairman of the ILRA board of directors along with Dennis Kerr. “We give deductions based upon safety, and we want to make sure that the linemen are working safe, and we want to find a way for people to have good work practices.”

Rotating Venues

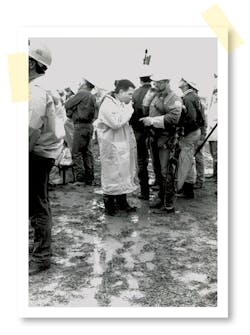

Over the years, the rodeo has moved to different locations in the Kansas City area, such as the Worlds of Fun amusement park grounds. For Rodney Lewis, general foreman of Portland General Electric Co., the 1994 rodeo specifically is still fresh in his memory. Lewis, who has competed at rodeos across the U.S. and assisted with the International Lineman’s Rodeo for 17 years, will never forget the mud from that year’s competition. “We had torrential downpours and flooding in the Midwest, so everything from the Missouri River past the Mississippi River was waterlogged,” he recalled. “The rain just did not let up.”

Back then, Lewis was a lineman for Public Service Company of Indiana, and he remembers boarding a charter bus from Indiana to Kansas City. On the way there, as he crossed the rivers, he saw major flooding. “When the day of the rodeo came, the sun came up on the Worlds of Fun grounds, which were down past the Ferris wheels,” Lewis said. “In the morning, there was about an inch of mud, but by the end of the day, there were places where the mud was up over your ankles.”

Of course, Lewis said this made the competition even more interesting for the linemen, used to working in tough conditions. Even so, it was quite a challenge for the 120 or so journeyman teams. “It just made it really hard, and it was very tough on our groundmen,” he said. “Everything was covered with mud — our climbers, tools and safety gear.”

On one of the events, the linemen had to build a closed delta transformer bank, and the hand lines became slathered in mud. “Everything was slicker than deer guts on a doorknob,” Lewis noted. “It made it even more challenging when it started raining and added to all of it. We had a fun time!”

Warman remembers when the grounds at Worlds of Fun were literally under water on Friday night and Saturday morning, and the volunteers had to move some of the events out of the flooded areas. “The weather has always been interesting,” he said. “We climb no matter what the weather is out because linemen are used to working in the storms and the rain. The only time they must come off the poles is if there is lightning.”

Along with competing for three years at Worlds of Fun, linemen also showcased their skills in the old Kansas City Stockyards district. In 1998, Jon Beasley, director of training and safety for MEAG Power and the Electric Cities of Georgia, remembers competing in a “big gravel parking lot with a nice downtown backdrop.”

While it was interesting for the crews to compete in such a historic area of town, there was not enough space allotted for parking nor the competition, Lewis added. “I was competing back then, and the events were right next to each other,” he recalled. “You could see everyone doing everything.”

The event at the stockyards marked the first time competitors were required to throw rope over the phases to simulate the wire down. Compounding this challenge, linemen had to contend with strong winds out of the west. “Needless to say, it was exciting for some of the teams and the apprentices,” Lewis observed. “We waited until the end of the day, and we had to deal with not only the wind but also trying to throw that rope over the phase 35 ft in the air.”

Moving to a New Location

In 1991, the rodeo moved to St. Louis, Missouri, in conjunction with the 100th anniversary of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEWs). Ameren Corp. volunteered to set up the rodeo grounds, and Warman and other volunteers helped them to prepare for the competition. That year, the rodeo doubled in size, and it doubled the year after. “After we had it in St. Louis and the IBEW got involved, we knew we couldn’t go back to the KCP&L training yard again,” Warman noted. “We totally outgrew it.”

After rotating to various venues, the ILRA moved the event to the Agricultural Hall of Fame grounds in 1999, where it still takes place today. “We had a golden opportunity come up,” Warman recalled. “The Agricultural Hall of Fame was trying to make funds to keep their doors open, and we moved the competition there, which is the best thing that could have ever happened. It’s a nice place where we can keep the poles up and not have to take them down every year.”

Through the years, KCP&L partnered with Westar Energy to help build and promote the event, according to KCP&L’s Putnam. In July 2018, Westar’s linemen changed out about 60 poles of the 187 poles on the rodeo grounds to prepare for the fall competition. He said the Agricultural Hall of Fame grounds is the perfect fit for the permanent location of the rodeo, and the volunteers are the ones who make the event successful. “There’s no place better,” Putnam said. “This event can’t move or travel without losing its soul.”

Putnam competed in 1991 as an apprentice lineman and took the Midwest regional champion trophy home that year. He then went on to compete at the International Lineman’s Rodeo. Since then, he has traveled to out-of-state rodeos to compete and volunteer.

During his time as a volunteer at the International Lineman’s Rodeo, he remembers running out of raw eggs, used for the pole-climb events. He had ordered 65 dozen medium-sized eggs and, after they were all gone, drove to QuikTrip to buy all the eggs in the convenience store. “I bought six dozen extra-large eggs, which were the wrong size for our competition,” Putnam said. “I ripped the egg carton covers off, so no one could tell what size they were, and we finished the day strong. Now we order 80 medium-sized dozen eggs, and we will never run out again!”

Putnam also recalls hauling water to the competitors’ tents, so they could cook meals, and trying to valet park trailers near their tents on muddy rodeo grounds. Also, he had to find a 110-ft steel transmission pole, set it in the middle of the grounds and hang a 50-ft by 30-ft American flag on it. Finally, he will never forget working on the grounds with his three best friends during a year when no one else from the utility was available.

Since Putnam was first involved with the rodeo, it has tripled in size. “It will remain the Super Bowl of rodeos,” he said. “The board and steering committee, and the sponsors who donate the products, make this event happen; it’s not because of me. As long as it stays rooted as an event for the linemen, it will succeed.”

Focusing on Safety

Warman said since the event has moved to the Agricultural Hall of Fame grounds, it has continued to grow and intensify as far as the level of competition. However, from the beginning, it always has been focused on safety. “Other competitions were based on how fast linemen could climb a pole,” he said. “We knew there was no way utilities would support it if they were taking a chance of their linemen getting hurt. From the beginning, our deductions were based upon safety.”

During the early days of the rodeo, linemen heard about the competition and would tell their boss about it. Their supervisor then would call Warman, who explained the rodeo helped linemen not only to practice line work but also do it safely.

Lewis remembers the first time he heard about the International Lineman’s Rodeo in the late 1980s. He was working for IBEW Local 42 in Massachusetts, and a team had just returned from competing in Kansas City. “Most linemen were athletes in high school and like competition,” Lewis said. “They told us, ‘You think you are a hot-stuff lineman, but you’re not. If anything will humble your lineman pride, it’s the rodeo.”

The competitors also told Lewis and the other linemen they learned different tips and tricks about safety at the competition. From his first rodeo, Lewis said it was drilled into him the competition was not about going fast but rather about safety. “We want to be able to leave work with everything we came to work with,” Lewis noted.

After competing in local and state rodeos, Lewis said the level of competition at the International Lineman’s Rodeo was much more intense. “Everyone has pride in the trade and wants to say that they placed in an event or won overall,” Lewis said. “The level of competition was a big slap in the face as a young lineman getting into it. The competition was so fierce.”

While linemen are competitive on the rodeo grounds, they also share a love for the trade and a special bond. “This is really a brotherhood and sisterhood, and the camaraderie was unbelievable,” Lewis said.

“Even though we compete against each other, we all talk amongst each other and tell each other what to watch out for during the competition.”

In addition, the competitors also get to showcase their skills in front of their families, which is a significant benefit. “Being able to take your family to see what you do all daylong is very special,” Lewis noted.

“They never get to see that. Due to liability and for other reasons, we can’t bring our families to work with us anymore. At the rodeo, they have the opportunity to see what Mom and Dad really do for a living.”

Lewis said it is hard to believe how much time has gone by since the first International Lineman’s Rodeo. “When I see all of the families there on a Saturday to watch or compete, it really makes the work that we all do that much more worthwhile,” he said.

The rodeo has come a long way since the days of the event at Worlds of Fun and the stockyards. “I know that I have always felt that the rodeo was like a big family reunion, and watching it grow over the years really enforces the sense of a great caring family,” he observed.

Stremel said over the years, the International Lineman’s Rodeo has been well represented by utilities across the U.S. and supported by the families. He feels fortunate the international competition is right in his backyard — just a four-hour drive from Hays, Kansas. “Many people have to travel a great distance to come and compete,” he said. “It’s great to catch up with them after competing against one another for year after year. We give each other tips and things to do.”

Climbing to the Top

Over the years, ILRA has made changes to the competition to level the playing field for smaller utilities. For example, in the beginning, the competition included the pole climb and hurt-man rescue, but it now also incorporates mystery events. “Every event is based on what they do every day, but only the master judges know about the mystery events,” Lewis explained. “They don’t know about it until they get their packets on Friday morning.”

The competitors do not learn about details of these mystery events until the day before the rodeo, leaving them little time to practice. However, the competitors often practice the other events as a team before they arrive in Kansas City for the big day.

For example, Lewis recalls when he was on a team, he practiced every night with his team for two or three hours starting at least two weeks before the event. “If you want to win, you better be practicing and communicating with your team,” he said. “You also need to learn from the linemen across the United States and other countries how they make their work safer and how they do their work practices.”

Beasley learned the importance of preparation firsthand when he and his team won the 1999 rodeo. After receiving the packet of information about the mystery events, he and his team practiced their mystery events that night in their room. “We got a bigger room at the motel, and we brought some stuff in our bags to practice and run through the events the night before,” he recalled. “People looked at us sideways like we were crazy when we carried all of our stuff up the elevators.”

Walking up on stage, however, made it all worth it. “I was older when I competed as a journeyman,” Beasley said. “I was 39 in 1998 and 40 in 1999, and I remember the chairman of the executive committee asking me if I was in the seniors event. I laughed it off, but it was sweet that night to win and be on top.”

At the awards banquet, Beasley knew he and his team had a clean run, meaning they had no deductions. As they sat in the back of the room, the announcer mispronounced their company name as Mega Power, instead of MEAG Power, and Beasley and his teammates just looked at each other. “We hadn’t been out at the rodeo that much, so I didn’t know if they were calling us,” he recalled. “The EMC that I grew up at applauded, but everyone else seemed to be like, ‘Who is this team?’ They all had matching shirts, and we had our own shirts on that we pulled out of our closets. We just eased in there and surprised everyone. That was a good deal.”

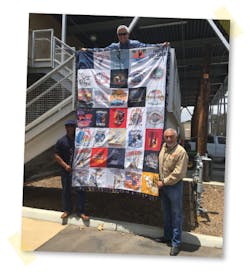

Beasley remembers not even having special T-shirts to swap at the annual T-shirt trade night, but he said other linemen were gracious to him and his teammates and said, “Here, take a shirt.”

Also, the other competitors from larger utilities brought an entire entourage with them to the International Lineman’s Rodeo. In Beasley’s case, however, it was only a small group—him, his two team members and a coach, along with his wife, the coach’s wife as well as a coworker who came to watch and shoot video. “There were only seven of us and, to beat the big guys, who brought numerous people to support them, was kind of gratifying,” he said.

To win the event took dedication and hard work, Beasley noted. For example, they tried a few tips and techniques that gave them the competitive edge. “You need to study the event to find out what the judges are looking for,” he advised. “If you don’t do what the judges want, that is not the deal. You must really listen and ask good questions. We would videotape ourselves practicing because you are your own worst critic. We would practice a few runs and see areas where we could speed it up, and it cut down our time big time and worked really well.”

The hard work paid off. Beasley, who has been in the industry for nearly 40 years, earned fourth overall in 1998, and then went back a year later to win the competition, besting the second-place competitor by more than 4 minutes, 8 seconds. “We won several trophies, and our company was very proud,” Beasley noted. “It was like instant credibility. We train for several cities across the Southeast and Georgia, and it showed that we really could do line work. No one walks on stage unless they are really good.”

To win the competition, Beasley said he and his team did not make any wasted moves. “The key is to be a good lineman and not be reckless,” he said. “You need to be smooth as silk and know what you are doing.”

Stremel said it also is important to be able to work well as a team. In 2014, his team took first place in the senior division and, in 2010 and 2017, his teams placed third. “It was rewarding competing against some of the bigger utilities in the nation,” he said. “For a small cooperative to compete against that caliber of people and take first or third was the highlight of my career.”

To get up on stage, he said it is important to practice a lot. Some years, however, it is not always possible to get together with teammates. The year his team won in 2014, they only were able to practice once. “We wanted to get together several times, but my pole buddies were working so many storms,” Stremel recalled. “When we did get together, we were only able to practice for an hour and a half because it was so windy. We had to break off early.”

But sometimes a team just gels and, even if they are not able to run through the events several times, they can still win a trophy. “Just being on a crew together gave us that meshing environment already,” he said. “I don’t work with those guys on a day-to-day basis, but we worked together for a number of years. We just click when we get back together again.”

Making Changes

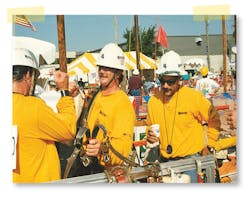

ILRA strives to make the competition fair for all by breaking up the contestants into different divisions, including investor-owned utilities, cooperatives, municipalities, contractors and military. In addition, ILRA also segregates the competitors into apprentice, journeymen and senior (over-55) events.

In addition, it now recommends competitors wear fall protection for added safety and to continue to make things fair for all linemen — whether they come from a small or large utility. “Everyone wears fall protection, and the competition has continued to be strong with the investor-owned, cooperatives and the municipalities,” Beasley said.

According to Stremel, at his utility, linemen have been in 100% full fall protection for four years. “At first, I thought it would hinder our times, but through our years of using it in our work activities, it hasn’t affected our times that much,” Stremel observed. “It is something we had to get used to. It was more of a mindset of trying to overcome than the physical task of being challenged to adjust to that change.”

At the International Lineman’s Rodeo, the focus has been and will always be on safety, Stremel said. “The focus is still on safety and demonstrating your skills to be an effective and safe worker when you do compete,” he explained. “The competition has never deviated from the emphasis that safety is important. In this trade, you don’t get a second chance and safety is No. 1.”

Showcasing Technology

In addition to competing at the rodeo, linemen also have an opportunity to learn about the latest technology and tools for the field workforce. “If you are working at a small municipal in a little city in rural America, what you don’t know, you don’t know,” Lewis noted. “When you go to these rodeos, you can talk to the other linemen, look at all this equipment, and tell your team back home that it would be very slick to have a certain type of equipment.”

In addition to selling out space at the exhibit hall for the Lineman’s Expo, ILRA also has added outdoor booths to the rodeo grounds in recent years. Stremel said this has been helpful for linemen. “If you don’t get around to every booth at the trade show, you can see some of them out on the grounds,” Stremel noted. “It’s interesting for the people at the rodeo to see what the lineman career and trade is all about as far as the tools, equipment and technology. In addition, some of the vendors help to sponsor the events at the rodeo by donating some of their equipment to the competition.”

For example, the sponsors of the 2018 competition include the IBEW, DragonWear, Hastings Hot Line Tools & Equipment, Jelco, J.L. Matthews Co., Bulwark FR, Columbus McKinnon Corp., Salisbury by Honeywell, Altec Inc., Buckingham Manufacturing and Glen Raven Inc.’s GlenGuard. Over the years, sponsors have donated millions in products used to build the rodeo events, Putnam says.

In addition, ILRA has invited vendors as well as linemen and safety experts to present at its annual free safety conference, sponsored by the IBEW. To plan this event, ILRA depends on its team of volunteers and board of directors from across the United States.

Stremel said the safety conference has become a great training resource for linemen, and it emphasizes safety prior to the apprentices and journeymen teams going out to compete. “We learn about different tools, equipment, technology and ergonomics as well as physical conditioning from the speakers,” Stremel noted. “We have even brought some of them into Midwest Energy after the safety conference to work with our linemen.”

Competing Locally

While the International Lineman’s Rodeo started as a single event, over time, it has spurred the creation of countless local, state and regional rodeos. Oftentimes, utilities host their own rodeos or sign up their apprentices and journeymen for nearby competitions to determine who will go to the International Lineman’s Rodeo in Bonner Springs.

For example, after Beasley and his team won overall in the 1999 competition, he worked with the vice president of engineering from the American Public Power Association (APPA) to kick off the APPA Rodeo, which is still going on today. For 14 years, he served as the master judge over all the events, before dropping off a few years ago to give younger linemen an opportunity to help.

Also, Beasley, who lives in Marietta, Georgia, was instrumental in starting the Georgia Rodeo, which just involved Georgia Power and the municipalities for the first few years. Eventually, Beasley was able to get the electric membership corporations (EMCs) he worked with on board. The statewide Georgia

Rodeo continues to grow.

Beasley said he will never forget the memories and connections he has made at all the rodeos during his career. “It is a big brotherhood, and the ones who I have competed against have become lifelong friends,” he said.

Warman said the International Lineman’s Rodeo takes an army of volunteers to execute the week of competition and camaraderie each year. Even when they retire from their jobs, the board of directors will cover the cost to fly back to Kansas City for planning meetings. “They do all that work without getting paid, because they believe in it and it’s a good cause,” Warman said. “We are all proud of where it went.”

From day one, the rodeo has been focused on the line trade and has not deviated from this mission, according to Warman. “The thing that has made the rodeo a success is that it has always been by the linemen, for the linemen and it will always be about linemen,” he explained. “There are no paid people — just volunteers doing it for the workers — and there’s no prize money. It’s for linemen’s right to get on that stage and have a trophy.”

Sidebar: Back in Time: A Roundup of Rodeo History

1983: The first U.S. National Lineman’s Rodeo was held at the Manhattan Vocational Technical School in Manhattan, Kansas, and organized by Tom White, president of TWSCO, a linework materials vendor; Dale Warman, a supervisor for Kansas City Power & Light; and Charlie Young, a supervisor for Southwest Line Construction.

1984: The rodeo was held once again at the technical college in Manhattan.

1986: After outgrowing the training grounds in Manhattan, the competition moved to the sub-zero training grounds of Kansas City Power & Light, where it stayed for five years.

1987: At the fourth annual event, apprentices competed for the first time. Also, a computer-based scoring program was used to manage the growing event.

1990: By its seventh year, the rodeo had grown from 36 competitors the first year to 235 competitors, nearly a 600% increase in participation. The number of utilities also increased from four in 1984 to more than 50 by 1990.

1991: The rodeo moved to St. Louis, Missouri, to coincide with the International Brotherhood of Electrical Worker’s (IBEW’s) 100th anniversary.

1992: The rodeo took place at the Worlds of Fun amusement park grounds in Kansas City, Missouri, for three years.

1993: The first teams from outside the U.S. competed at the rodeo. Teams from Canada and England entered that year, followed in later years by competitors and representatives from other countries such as the Philippines, Jamaica, Ireland, Germany, France, Russia and South Africa. In addition, the rodeo board of directors formed the International Lineman’s Rodeo Association (ILRA).

1995: The rodeo moved to a vacant lot in the Kansas City Stockyards district.

1996: The ILRA organized the competition at a location in the West Bottoms area of Kansas City.

1998: The ILRA entered an alliance with the publisher of T&D World magazine to set up a Lineman’s Expo and handle other activities. For example, Richard Bush, who recently retired as the strategic director of the magazine, came up with the idea for the annual safety conference to set the event apart from other rodeos, and Kim Good works with the exhibition team and the ILRA to organize and execute the event each year.

1999: The ILRA was granted nonprofit corporation status in the state of Missouri. Also, the board of directors contracted with the National Agricultural Hall of Fame for a lease on open land in Bonner Springs, Kansas. The rodeo still takes place there today.

2007: The City of Overland Park and the Overland Park Convention Bureau honored the International Lineman’s Rodeo Association with an award for bringing business and tourism into the community.

2018: The rodeo celebrates its 35th anniversary. Along with the daylong competition, the ILRA also offers scholarships for future linemen, provides a free day-and-half safety conference, organizes a T-shirt trade night and lineman’s barbecue, and works with Informa on a multiday trade show called the Lineman’s Expo.

Source: ILRA

About the Author

Amy Fischbach

Electric Utilities Operations

Amy Fischbach is the Field Editor for T&D World magazine and manages the Electric Utility Operations section. She is the host of the Line Life Podcast, which celebrates the grit, courage and inspirational teamwork of the line trade. She also works on the annual Lineworker Supplement and the Vegetation Management Supplement as well as the Lineman Life and Lineman's Rodeo News enewsletters. Amy also covers events such as the Trees & Utilities conference and the International Lineman's Rodeo. She is the past president of the ASBPE Educational Foundation and ASBPE and earned her bachelor's and master's degrees in journalism from Kansas State University. She can be reached at [email protected].