Technology and technical advances are changing just about every field of work today, something that is certainly true for vegetation management. Big data, light detection and ranging (LiDAR), and drones are just three of the advancing technologies utilities are either currently using or considering using in the future to keep the power on, manage their vegetation better and, importantly, learn from and track their efforts.

Big Data

First, on the ground level, utilities and cooperatives across the country are taking advantage of ever-more powerful and precise vegetation management data systems. A good example is the Arborcision program used by Chris Byrnes, an arborist from ACRT who directs vegetation management efforts at the Lake Region Electric Cooperative (REC) in Pelican Rapids, Minnesota, U.S.

Lake Region, situated in northwestern Minnesota’s lush lake country, covers some 3,200 sq miles (8,288 sq km) with 5,700 miles (14,763 sq km) of line, serving a population of about 23,000 members, including 7,000 seasonal homes strung along the more than 1,000 lakes in its service territory.

Byrnes captains the REC’s vegetation management team using a program that provides statistical analysis unheard of even a few short years ago. Arborcision, run as a software-as-a-service platform, lets Byrnes see the company’s service territory as a whole; drill down on any trouble spots to an individual tree circuit level, and track systemwide tree pruning and removal cycles. Using Arborcision, Byrnes can quantify systemwide vegetation management efforts, plan such efforts into future years and even compare his system with those of similarly-sized RECs and utilities in the nationwide Arborcision database who have uploaded their data.

What makes programs like Arborcision so powerful is not only the collective size of the data gathered but the analytics Byrnes can run.

“On any circuit, I can see fast-growing trees, low-growing trees, how far trees are from the line,” Byrnes noted. “It can show me two or five years out how far this tree is expected to grow and whether that will still be outside our clearance.”

Using Arborcision, Byrnes also can identify and call up member contact information along a circuit, something he says helps when the REC needs to reach its customers regarding vegetation matters, a particular benefit in Lake Region’s case, since many REC members live elsewhere and use their Lake Region lake homes and cabins primarily in the summer months.

The results of using big data and advanced data analytics speak for themselves, Byrnes claims. He says that when compared with the Lake Region’s vegetation management efforts five years ago, Arborcision use has resulted in a 45% decrease in outage hours and a 30% reduction in tree-related outages. Program usage has dropped time spent hot-spotting from 50% in 2009 to just 5% to 10% last year.

The REC’s annual vegetation management budget has dropped from US$2 million in 2009 to an estimated $500,000 in 2015. Perhaps best of all, adds Tim Thompson, Lake Region’s CEO, the company has managed to forestall any rate increases over the past year and has actually given back $1 million to members in capital credits.

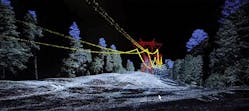

LiDAR from Above

Technology also is changing and improving vegetation management from above. A good example is the increased and expanded use of LiDAR for line planning and ongoing maintenance, in particular since the introduction of the NERC FAC-003-3 reliability standard in July 2014. LiDAR-equipped helicopters have flown the majority of the 100-kV and higher transmission lines in North America, says Chuck Anderson, general manager of North American utilities for GeoDigital International.

“LiDAR is a laser-range finder on steroids,” Anderson explained. “It’s basically a scanner looking down over the treetops and lines, and taking about 300,000 to 500,000 measurements per second. The relative accuracy levels are terrific. A tree that is measured at 100 ft tall will be 100 ft ±5 cm — you can count on it.”

With that accuracy and all those images, utility vegetation managers can then add biometric information and model existing vegetation along a future path to see where, how and when it might impede power delivery or take down a line. Biometric data includes not only tree height but also can include attributes such as density, type of tree, anticipated growth pattern and tree status (healthy, diseased or dead). Weather conditions during data gathering can be added, including wind speed, wind direction, relative humidity, air pressure and even sun intensity.

LiDAR has even advanced to the point where it can use orthographically registered true-color and infrared imagery to summarize the reflectance of the canopy, thus assigning health codes to trees. Other opportunities include measurement and estimation of fire fuels risk based on tree size, type, location and health, or the tracking of insect and wildlife threats around lines, in rights-of-way and around structures.

Anderson says that while LiDAR is becoming widely used for transmission line scanning and planning, it also is finding a place in distribution planning but in a somewhat less obvious way. “We are using it to map highways for the driverless vehicle program,” Anderson observed. “As we map the highways, we also capture the distribution assets along roads. We are getting pole locations, structure types and vegetation clearances.”

The Dawn of the Drones

Perhaps one of the hottest tech topics in utility vegetation management technology in the coming years will be the use of unmanned aerial vehicles — drones — for line surveys and repair.

“There’s a lot of energy and excitement, and we are working with a couple of drone companies and developing integrated solutions for our utility clients,” Anderson said. “Clients value the spectacular imagery drones can capture, and we are now focusing on turning this imagery into actionable, integrated, business intelligence that goes beyond the ‘wow factor’ and actually solves a business problem.”

“Drones outfitted with LiDAR may be coming,” concluded Randall H. Miller, director of vegetation management of PacifiCorp, adding he understands drones have been used successfully for vegetation management by utilities overseas. “There is no approval from the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) right now for drones, but it looks like it may be coming.”

In fact, the FAA did grant San Diego Gas & Electric (SDG&E) limited permission to use drones in parts of San Diego County, California, U.S., in July 2014. SDG&E, a Sempra Energy utility, was the first utility in the nation to be granted FAA approval for the technology.

SDG&E got what is called a special airworthiness certificate for a small unmanned aircraft system. That certificate specifically allowed SDG&E to use drones for research, testing and training flights in sparsely populated airspace in eastern San Diego County. Since July 2005, the FAA has issued 94 such certificates to 13 civil operators. Last year, Amazon also asked for such a certificate to test small-package delivery with drones. SDG&E used the permission to test a small drone measuring 16 inches (406 mm) in diameter and weighing less than 1 lb (0.5 kg) for gas and electrical line inspections.

In terms of vegetation management, drones offer clear advantages over manned helicopter flights for line and rights-of-way surveys.

As Anderson notes, they are cheaper to fly and can stay up in the air for extended periods of time. Their light weight means drones use only a fraction of the fuel of a helicopter, and their small size and maneuverability allows utilities to see into places that might be harder to reach with a larger manned aircraft. Drones also are quieter and have a much smaller environmental impact than manned aircraft, not to mention bringing down insurance rates and improving safety simply by not having someone up in the air.

Further advantages to drones over manned flights would be the ability to reach and cover wide swaths of lines that cross rural properties, as well as the ability to maneuver around and in between tight areas in urban settings.

But drone advantages also are seen as drawbacks at this point. Among the issues the FAA must resolve, according to both Anderson and Miller, are privacy issues and line-of-sight restrictions. As it stands at present, Anderson explains, drones must always be in clear line of sight, which does not work for utilities that would be flying drones over lines towered over by tall trees. “You’d have to have someone standing on the ground in the right-of-way every few hundred feet to keep line of sight,” he noted.

Drones equipped with cameras also raise privacy concerns, and the fact that drones are nearly silent raises the privacy stakes even a bit more. The FAA is probably rightfully concerned about the public perception of permitting fleets of small, silent unmanned vehicles to fill the skies.

Just outside Denver, Colorado, U.S., though, Chris Vallier, CEO of UAV technology company FLoT Systems, says his company is currently operational on several different FAA-approved missions for a couple of different utilities, solving issues that either can’t be solved with traditional helicopters or are too dangerous to do so. He calls the smaller drones that most people are familiar with “one-pole wonders” that generally will be used for smaller-scale, very localized missions. His company will offer that as well as larger vehicles that have longer-range capabilities and can even carry larger payloads like LiDAR. “The question becomes, what are you trying to do?” Vallier asks. “Do you want to sit in one spot and watch a piece of infrastructure over time, or do you go solve problems that cover a large part of your network after a storm?”

Vallier adds that the utility business model for drones is still being developed, but he sees at least two paths: one involves utilities owning their own small drones and another has them leasing services from companies such as his that can provide licensed pilots and the advanced technical capabilities needed for vehicles that can fly farther or stay in the air longer. FLoT Systems, Vallier adds, is focused purely on utilities. “The one thing I would avoid in a UAV company is one that says they want to provide a whole range of services for a whole group of industries or companies,” Vallier advises.

“People have not looked at it from the business standpoint, because when you do, the economics are eventually going to favor drones,” Anderson concludes.