Spring is well underway. It is the time of year for floral blooms and warmer temperatures. It is the time of year when folks start dreaming about their summertime adventures. It is also the time of year when the bleak, skeletal appearance of the urban forest is rejuvenated by the new canopy that will shade and beautify neighborhoods and parks. For some cities in the east and central states, those rejuvenated landscapes will arrive with somewhat lesser fanfare than in previous years, and the culprit is not unknown to those who manage them.

The emerald ash borer (EAB) is a wood-boring beetle indigenous to countries in northeastern Asia. It was identified as the killer of ash trees in southeastern Michigan. The damage that resulted in the years after its discovery was aggressive and extensive, with tens of millions of dead ash trees reported in 13 states, so far. What is new for these eastern and central cities, such as Columbus, Ohio, and Indianapolis, Indiana, is that the damage will be very evident, whereas before it was only suspected and anticipated.

Unlike many other wood-boring beetles, EAB aggressively kills ash trees that are healthy and unstressed, resulting in death within two to three years after infestation. Studies have shown that in test areas with 87% of their ash tree population with full to nearly full crowns, 98% of those ash trees will be totally leafless in five years. Other research indicates that, after two years, limbs of the larger trees will start breaking off, and, after four years, the larger trees will typically fail at the base of the tree at ground level. Such rapid decline creates a certain level of urgency for trimming or, more often, removal along power lines.

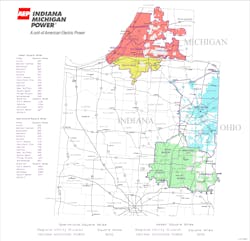

Staff foresters working for Indiana Michigan Power (I&M), a subsidiary operating company of American Electric Power (AEP) that serves 582,000 customers in northeastern Indiana and southwestern Michigan, have witnessed the damage firsthand. The EAB infestation began at an epicenter in Canton, Michigan, and spread uncontrolled at a rate of 10.6 km (6.6 miles) per year. The utility knew it would only be a matter of time before the infestation invaded I&M’s service territory. At present, the damage is very evident and widespread across all districts of I&M.

It was this sense of urgency that led I&M forestry to perform a survey of ash trees to study the potential impact to its distribution electric system. The goal of this study was to analyze the threat imposed by the infested and damaged ash trees, inventory the total ash population along the distribution system and estimate the fiscal impact I&M would potentially face.

In the fall of 2011, I&M and its contractor Asplundh Tree Expert Co. sampled the entire service territory as part of a full study. The purpose of the study was to determine the extent of EAB threat and damage within I&M’s service territory, as well as to estimate the resource requirements (dollars) necessary to address the damage and alleviate the threat.

To achieve a 95% confidence level, the survey had to encompass 375 miles (604 km) of the 16,650 overhead distribution line miles within I&M. Line miles were translated to pole spans using an average of 26 spans (pole to pole) per mile, totaling 1,200 eight-span plots. I&M operates four districts of comparable line miles (Fort Wayne, Muncie and South Bend, Indiana, as well as Michigan), so it was agreed there would be 300 eight-span plots randomly selected in each district.

The criteria for the survey fell within three categories:

- Location parameters (for example, county, GPS position, ownership, wire zone)

- Tree characteristic parameters (for example, diameter at breast height (DBH), height, growth characteristics, lean, mortality)

- Maintenance factors (for example, in or out of right-of-way, accounting class, truck accessible, threat potential, maintenance)

The information and data gathered in the survey was arranged in multiple variations: location of trees by service areas, DBH category of trees, type of additional work, location on the system (feeder breaker zone, multiphase or single phase), the accounting classification of projected tree work, tree location (inside or outside of the right-of-way). Additional information was collected: whether the tree is on private or public land, whether the tree threatens personal property and the percent mortality of the tree.

Once the data was organized, cost was applied to each tree. The costs applied depended on the size of the tree, amount of additional work needed, and whether the tree was lift or manually accessible.

The breakdown of data classifications for ash trees was precise and allowed the sample to be extrapolated to project the impact over the entire I&M distribution system.

Ash Tree Numbers and Distribution

Based on the sampling data, foresters estimated there are 51,600 ash trees along the entire I&M distribution system, with 35,000 posing an immediate threat to overhead lines based on their mortality.

Ash trees make up 7% of the total tree species within I&M. In the Fort Wayne district, the proportion is 12% of the total species. There are approximately five ash trees/mile, on average, in the Fort Wayne district and, as an urban-setting comparison, the ash tree average rises to 10 per mile for the city of Fort Wayne proper.

Of those ash trees surveyed that could likely impact I&M’s system, 81% were found located in single-phase wire zones, which are typically 20 ft (6 m) wide. In contrast, only 4% were found in the feeder breaker zones, a testament to I&M having focused its clearing efforts on the feeder breaker zones to protect the highest number of customers per outage. Since the single-phase zones are narrower than multi-phase or feeder breaker zones, the proximity factor plays an important role. A tree that could fall in any direction is more likely to hit the line the closer it is to the line. As it turns out, 96% of the trees sampled were actually outside the right-of-way. Since these trees are considered threats to the line, it is apparent ash tree maintenance will require I&M to extend beyond the width defined for single-phase zones in the utility’s clearing specifications, to alleviate the threats. This is an added difficulty for I&M since the majority of its lines are built on roadways or city easements that do not necessarily address or give legal rights to clearing trees outside the easement descriptions.

Proactive Maintenance vs. Outage Response

Based on the survey data analysis defined earlier, the estimated cost of proactive maintenance to alleviate the ash tree threat for the entire I&M service territory is approximately US$19.6 million. Since the survey looked at ash trees requiring work beyond normal maintenance, these dollars would be additional to annual allocated budget dollars.

By contrast, the typical cost of a tree-caused outage in 2011 was $859 (response only, not including loss in revenue). This cost covers line crew and tree crew support based on the amount of need for those resources as shown in the data. Using this cost, and considering the number of ash danger trees, I&M faces a potential restoration cost of $30 million due to EAB.

In 2011, trees accounted for 21.3% of the outages recorded by I&M in Indiana and 39.5% of the outages in Michigan. Of those tree-caused outages, 40% resulted in wires down, with an average of 3.8 hours/tree-caused outage. This kind of damage can be anticipated with trees that have been infested with EAB, since these trees die fast, resulting in the weakening of large sections of wood that could potentially fall into power lines.

Additional Considerations

It is important to look at the safety factors when considering the benefits of a proactive response. Once an ash tree has reached a certain point of decline, tree personnel cannot safely climb into the crown to do their work. The I&M data shows that 44% of the trees that will require work are not lift-truck accessible.

Also, when ash trees are in heavy decline, removal is difficult. The hinge wood associated with safe tree felling is not as dependable when the wood has desiccated. Further, the dead branches overhead create hazardous line-of-fire issues within the work zone. Adding to the risk is an increase in the number of times civil authorities are called to guard the downed lines while I&M responds. Clearing power lines that are entangled in trees creates many safety issues, including stored energy hazards.

The survey also looked at ash trees on the system that threaten personal property. Results showed that about 7,800 ash trees threaten nearly 5,900 different properties. Therefore, about 22% of the ash trees that threaten power lines also threaten some type of customer-owned property. An Ohio study showed that the mean price for a customer to have a qualified private contractor remove a tree ranged from $300 for a zero to 12-inch (zero to 30-cm) DBH to as much as $2,000 or more for one 36 inches (91 cm) and greater.

In Conclusion

There are success stories within the urban forestry communities, particularly in the municipalities and local governments where most, if not all, of the ash trees are inventoried and, generally speaking, reside along streets where access is good. That being said, these trees still have the potential to become threats nonetheless, and the threats are being properly addressed. Management within the municipal organizations is responding with a willingness to fund programs in response to these threats. For instance, in Ohio, 29 communities received federal aid to remove ash trees on top of the money allocated by their own local funds. The City of Fort Wayne generously funded ash tree removal in 2011 and earmarked even more for 2012.

There are treatment programs in place to try to sustain the population of urban ash trees. There is marked success in this program, but there are limitations to achieving and maintaining that success. This is a subject worthy of research for those who would consider it.

As this report has shown, the cost to perform the maintenance on these ash trees alone is extreme for a utility the size of I&M. Many utilities are larger and cover more difficult terrain. Often there is the added pressure to remove ash trees that threaten adjacent personal property, but not power lines. While this is not the responsibility of the utility, it casts an incorrect negative perception toward the utility’s concern and customer focus.

Customers should understand that any work performed by their electric utility on a dead ash tree, whether it is total removal or not, is work they do not have to pay for. Removing trees that only need trimmed or need no work at all would be an unjustified cost to the utility and clearly at odds with the will of the commissions. This does not mean I&M and other electric utilities are not sympathetic to the customers’ situation.

Based on the research and data provided, it is logical to predict that all untreated ash trees within I&M’s distribution system will be dead in four years or sooner, depending on their current state of mortality. That being said, taking the proactive approach to these trees is necessary because it is not a matter of if but a matter of when.

Many utilities have plans in place to spread the cost over a number of years. The annual reactionary cost on a 10-year plan is $3 million, an additional $1 million/year more than the proactive plan, because the spending would shift from proactive to reactionary after four years into a 10-year plan. The cost would increase even further on an annual basis because of the heightened reactionary urgency and increased damage potential of trees that fail at the base. Research clearly shows these trees simply will not remain standing for 10 years.

I&M is required to make annual reports on the reliability indices of the system average interruption frequency index (SAIFI), customer average interruption duration index (CAIDI) and system average interruption duration index (SAIDI) to the Indiana Utility Regulatory Commission (IURC) and the Michigan Public Service Commission. In addition, there is an annual vegetation management report required for the IURC that includes customer complaints related to tree trimming, as well as the percentage of tree-related outages compared to total outages. If either of these metrics increases notably, or reaches unacceptable levels as a result of these ash danger trees, there could potentially be a negative reaction from these commissions.

Utility foresters understand the need to manage limited financial resources to provide reliable service to all customers. This budget management makes it a challenge to apply sound judgment specific to dead and dying ash trees near power lines. With this strict budget management in mind, project managers and foresters should consider this type of survey. It provides detailed information that upper level management and regulatory commissions can look directly at without speculation. It is the kind of information that supports a specific argument. In this case, it is an argument that will lead to an end result that truly is inarguable.

Acknowledgment

Special thanks go to Mike Maskal of Indiana Michigan Power and Zack Murray of EDKO LLC for their help with this project.

About the Author:

Scott Bennett ([email protected]) is a former forestry supervisor for Indiana Michigan Power. He has worked more than 20 years as a utility forester in both electric transmission and distribution fields. He earned his bachelor’s degree in forestry at the University of Kentucky. He served as the president of the West Virginia Vegetation Management Association and is currently on the board of directors of the Indiana Arborist Association. He is an International Society of Arboriculture certified arborist and certified utility specialist. He was recently appointed manager of distribution systems for the Muncie district of Indiana Michigan Power.